Corinne or Italy as a travel guidebook

How was Staël’s novel Corinne or Italy born?

Public Domain

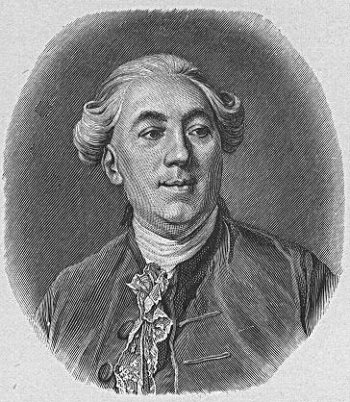

Just before she died, Staël described what she cherished most in life as “God, my father, and liberty.” This attests that her father, Jacques Necker, was a huge presence throughout her lifetime.

While in Germany in 1804, Staël was informed of the death of her beloved father. She then planned a trip to Italy to heal from her loss. At the end of 1804, she embarked on a six-month journey to Italy with her three children and their tutor, a famous German literary critic, August Wilhelm Schlegel.

Staël eventually published her impressions of Italy in 1807 in a novel entitled Corinne or Italy. The book was an immense success across Europe, and she eventually became a writer of international caliber.

Public Domain

Corinne or Italy is a romantic and tragic love story set in Italy.

The main character, Corinne, was born in Britain from a British nobleman and his Italian wife. However, she decides to leave her home country and live in Italy in order to exercise her artistic talent. She eventually becomes a poet and improviser.

However, the happiness of the young artist does not last long. Corinne falls in love with a Scottish nobleman named Oswald in Rome. Oswald eventually chooses to marry a homely woman—incidentally, Corinne’s half-sister—and Corinne despairs, withers, and finally dies.

Public Domain

The romance story of the couple in Italy develops during the journey. Corinne volunteers to serve as a tourist guide for Oswald, and together they visit Rome, Naples, Venice, and Florence, enjoying Italian culture and people.

For this reason, the novel contains occasional descriptions of Italian history, cities, nature, ruins, customs, and even Italians’ social mores. They are an integral part of the novel insofar as they match the emotional inflections of the characters.

At the same time, a prominent characteristic of Corinne is that tourism in Italy constitutes an independent theme through these descriptions.

In the nineteenth-century, many French tourists put Corinne in suitcases as a guidebook for traveling to Italy. This was so to such a point that Corinne was conventionally classified as a tourist guide rather than a novel in libraries in France. Corinne as a tourist guidebook was indeed highly appreciated by the French.

Corinne and Napoleon

When Staël wrote Corinne, Napoleon dominated many parts of Europe, and was expanding his territory even farther by war.

By Thesupermat

In 1797, Napoleon signed the Trentino peace treaty with Pope Pius VI who ceded his territory. About a hundred artworks, such as Raffaello’s paintings, were taken to Paris from the Vatican Palace. Napoleon exhibited them along with other artworks confiscated from various regions at the Napoleon Museum in Paris, now the Louvre.

By contrast, Napoleon also built in Paris Carousel’s Arc de Triomphe and the Vendôme column in order to turn the French capital into a “new Rome” in continuity with the Ancient Roman Empire. This way, Napoleon highlighted that as the French emperor he was also a modern successor of ancient Roman emperors.

Public Domain

In Corinne, Staël stealthy contested Napoleon’s way of looking down on Europe with France at its center and his suppression of European countries by military force. However, some of her tactics may go unnoticed: for example, Corinne is set in Italy in late 1794, well before Napoleon brought back numerous paintings and sculptures to France. Artworks possessed by the Vatican Museum of Art that had been looted by Napoleon are fictionally returned to Italy in the novel.

At the same time, not unlike Napoleon, Staël also regards Rome as the starting point for the universal human history, as it were, that has been unfolded up to their present day. While being conscious of the profound transition since then, in the novel, she laid emphasis on placing Italian paintings and sculptures of various periods as part of the Italian contemporary climate, unlike the Corsican ruler.

This attitude meant several things.

For one thing, it reminds readers that Italy, ruled by Napoleon and deprived of much of its cultural heritage, at the present possessed a glorious history of its own as well as a promising future.

To feel Italian history and ruins in which the long-distant past fused perfectly with the current time would help French readers connect with deep parts of their own identity that had been physically and mentally mutilated by the French Revolution and war.

From this viewpoint, a journey to Italy was a healing trip to the French as was the case with Staël, herself. In Italy,

poetry and history are brought to mind, and the charming sites that recall them soothe all that is melancholy in the past.※1

At the same time, Staël meant to encourage a nascent national unity among the Italians by awakening their national consciousness through sharing a common cultural heritage and history since the classical Roman Empire.

Travel and happiness

Thus, one of the central themes of Corinne obviously is travel.In this regard, the novel reflects Staël’s own personal life, composed of intermittent travels.

From a young age, Staël frequently traveled between Paris and Switzerland, where her parents’ castle was located. After the Terror started, she escaped France and went into exile in England and Switzerland.

Later, during the Directory, she was temporarily ordered into exile, and even after her exile was lifted, Staël was obliged to go back and forth between Switzerland and Paris, depending on the delicate political situation in France.

In 1802, Staël tested her chance again, returning to Paris and resuming the political salon, but Napoleon, the first consul, did not like any of her ideas and ordered her to leave Paris.

Staël transformed her humiliation into an opportunity and energetically traveled to Germany and Italy, among other places, to expand her intellectual and cultural horizons. She eventually published her works on German and Italian culture and national character (On Germany and Corinne or Italy), which was hardly known in early nineteenth-century France.

Napoleon officially exiled Staël to Switzerland in 1810. By that time, it was no longer possible for her to open a salon or publish her opinions. Strictly confined to her family estate in Coppet, Switzerland, and deeply despaired, Staël secretly decided to leave for England in 1812.

Staël finally arrived in London the following year via Austria, Bohemia, Moravia, Kiev, Moscow, St. Petersburg, and Sweden. In 1814, when Napoleon’s empire collapsed, Staël finally returned to Paris and resumed her salon in Restoration France, only briefly resuming her exile during the Hundred Days.

Thus, from the French Revolution to the imperial period of Napoleon, Staël lived a life constantly dominated by travel and exile.

Still, Staël’s most favorite place to stay remained Paris where she spent the happiest of her time from childhood to adolescence. So, the perspective of not being able to live in Paris while either traveling or exiled was indeed a melancholic experience for her.

Staël’s personal background must have influenced her unique definition of travel, although it is also applicable to many of us, as well.

Whatever people may say, travelling is one of the saddest pleasures in life. When you feel comfortable in some foreign town, it is because you are beginning to belong to it; but to cross unknown countries, to hear people speak a language you barely understand, to see human faces that have no connection either with your past or your future, means loneliness and isolation without peace and dignity.※2

Meanwhile, this is how Staël wrote about happiness:

Happiness is necessary for everything and the most melancholy poetry has to be inspired by a kind of vigour which assumes strength and intellectual pleasures. Genuine grief is by nature infertile. What it produces is only a gloomy restlessness—which continually brings one back to the same thoughts.※3

As you can imagine from these two sentences, the journey, although defined as “one of the saddest pleasures,” is decisively a source of happiness for Staël. This is because, according to Staël, even in a situation that is objectively and physically difficult, a talented artist can replace it with inner happiness by using it as a source of creativity. And the attitude of choosing to live positively like that was “freedom”. This is how Staël eventually transformed it into numerous powerful books that have remained valid until today.

Public Domain

The infinite and the finite

Lastly, I briefly present the worth of Corinne as seen in terms of our contemporary travel guide to Italy.

To put it simply, Corinne invites us to the philosophical world of the eighteenth century through a journey to Italy.

Philosophy does not mean anything obtuse or complex in Corinne. It just helps you to think about the theme of life that emerges in extraordinary days, meaning travel, away from everyday life.

A major theme that runs throughout the novel is a contrast between life and death, finite and infinite, present and past. Through Staël’s eyes, travelers are forcibly reminded of the gap between unchanging landscape and ever-evolving “life.”

Picture taken by mysef : “Mostra Fantasmia

Pompei” by Dario Assisi and Riccardo

Maria Cipolla in National Museum of

Naples, 2018-2019

Staël is decisively more interested in history and ruins rather than nature. However, life factors such as water, flames, sun, and plants in the novel always remind observers that history and ruins are indeed present with us today.

For example, in Naples, even the ruins that have endured the passage of time have become parts of the beautiful landscape today, thanks to the presence of “moving flowers and trees” that surround them.

Meanwhile, the center of Italy’s travel in Corinne is obviously Rome.

In other towns, you need to hear the din of carriages, but in Rome it is the murmur of this enormous fountain which seems the necessary background to the daydreaming life you lead there.

With constant murmurings of numerous tourists visiting from morning till night, the Trevi Fountain certainly is NOT a quiet spot where you could possibly hear water fall today.

Even so, could you just give a momentaneous thought as to what Rome would have looked like in the early nineteenth century?

Staël’s casual depictions such as these would help travelers distinguish the ancient, eighteenth-century Roman, present, and cultural and historical shifts in the ruins, buildings, and even artworks.

After walking for a while around Rome, the traveler might stop and be stunned. This is when he or she might come across the idea that he or she is a traveler not just in Italy but also in this world.

That might be my own case as a non-Christian. For Staël, who deepened her Christian faith as she matured in life, there was decisively eternal life beyond her death.

The “special feelings” to be created by an original fusion of the rich nature and history in Italy and conveyed by Corinne are therefore alive today if we are to try to stretch our imagination a little further.

However, it is definitely up to each and every individual to recognize how he or she would feel from personal experience and imagination.

Staël’s philosophical tourist guide therefore has no conclusions. Readers can enliven their versions of 19th-Century Romantic Italian Travel this way.

On this site, I have posted numerous pictures of my travel to Italy along with quotes from Corinne.

It is strictly prohibited to copy or take pictures without permission.

- ※1Ibid.book XI-I, 187.

- ※2Madame de Staël Corinne, or Italy, trans. by Sylvia Raphael, (Oxford University Press, 1998), 9.

- ※3Ibid.356.

- ※4 Ibid.74.