Public Domain

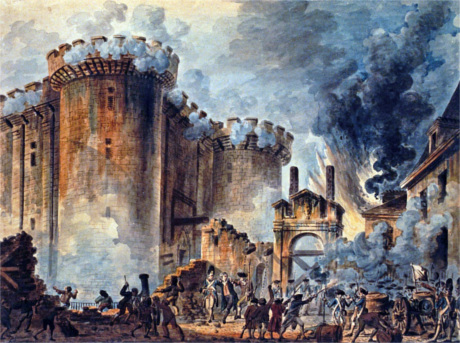

Staël and the French Revolution

Public Domain

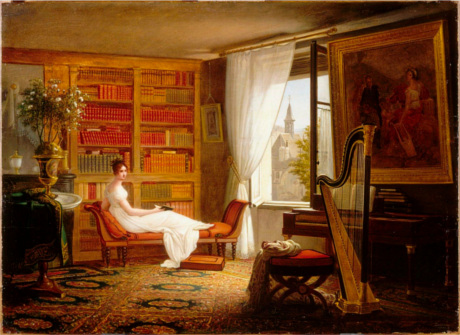

Mme de Staël (Anne-Louise-Germaine Necker, 1766–1817) was born in Paris as the only daughter of Jacques Necker, who served as the minister of finance for Louis XVI during the absolute monarchy and Revolutionary France. Germaine attended the salon held by her mother since her early childhood and had the opportunity to talk with key intellectuals who epitomized the French Enlightenment. Despite the absence of a formal school system for French upper-class girls at the time, Germaine was exceptionally blessed with the opportunity to gain knowledge similar to that of upper-class men thanks to conversations at the salon.

Born a commoner, she married the Swedish ambassador M. de Staël-Holstein in 1776 in Paris after being introduced by the French royal family, and thus joined the nobility. After her marriage, Staël opened her own political salon. As a result, when the French Revolution broke out, Staël would witness this unprecedented political event from within the circles of power, both as Necker’s daughter and as the Swedish ambassador’s wife.

Public Domain

On July 14, 1789, the “Bastille Prison Raid” broke out. Paris citizens who repelled the king’s convocation and the removal of Necker rallied the militia and attacked Bastille. Staël has supported the French Revolution for a lifetime since this time. For her, the incident was not just the beginning of the French Revolution, but an eternal testament to the bond between her own father and the citizens of Paris.

Public Domain

During the Revolutionary decade between 1789 and 1799, she tried incessantly to gather moderate members of revolutionary and counter-revolutionary groups in her salon in order to find a compromise between them, consolidate a political force of moderation, and terminate the French Revolution. However, these ideas were still premature at this historic stage. Consequently, beyond showing any interest in her ideas, a large bulk of her contemporaries, both revolutionaries and counterrevolutionaries, turned hostile. By 1799, Staël was completely isolated from all political groups, and they watched her with caution.

Staël as a Writer

Staël’s gift as a conservationist also made her a well-reputed female writer, exerting wide-spread influence over French and European public opinion. Over her lifetime, she published more than 10 works of fiction, political essays, and philosophical reviews, all with political intent. Her works were meant to easily end the disruption of the French Revolution and build a modern society based on freedom and order.

In 1800, Staël offended Napoleon, who had just assumed power, with her literary criticism and a novel that critically alluded to him. These writings deteriorated her relationship with him in an irreversible manner. Not tolerating women speaking publicly about politics, Napoleon eventually decided to expel Staël from France, and she was forced to live in her father’s castle in Coppet, not far from Geneva, in Switzerland. Eventually, Staël had to live in exile for over a decade.

For Staël, this was a more tormenting experience than could be imagined. In her own words, “not breathing the air of Paris was an unimaginable suffering.” Staël, who had been born and raised in Paris, the cultural center of Europe at the time, was able to realize the joy of life only by deeply connecting with people through conversation,

Public Domain

Moreover, in 1803, Staël was informed of the sudden death of her beloved father while traveling in Germany. Seriously affected by this loss, she decided to embark on a journey to Italy. She eventually turned this six-month healing journey into a novel entitled Corinne or Italy in 1807.

As a result of the success of the book across Europe and the similar success of a literary and cultural piece entitled, On Germany (1813), Staël eventually became a female author of international reputation. She returned to Paris upon the restoration of the Bourbons in 1814 only to die three years later in 1817 at the age of 54.

Staël and French Enlightenment

Staël is said to be the last woman philosophe of the generation of the Enlightenment. She highlights the notions of civility and moderation in Enlightenment philosophy. She was therefore critical of the political culture of the French Revolution, which tried to build up an entirely new society from scratch by emphasizing principles such as “equality” and “philosophy” at the expense of “freedom.”

For the same reason, Staël was critical of the principle of national sovereignty, which rejected all “traditions” from the aristocratic hierarchy to the pattern of land ownership, and totally denied the past and the pre-existing social and economic conditions.

Staël exposed her liberal political ideas through a history of the French Revolution in Considerations on the French Revolution, published after her death in 1818. She divided the historical process from 1789 to the Terror into two periods, giving rise to what is known today as a liberal interpretation of the French Revolution.

The first period starts with her father, Jacques Necker, proposing a bicameral parliamentary system to the king and ends with the Storming of the Bastille by Parisians in July 1789. Staël considers this period to be a legitimate historical process of political institutionalization of liberty, even though it failed.

Staël then rejected the subsequent phase as an illegitimate phase of the French Revolution: After the National Assembly was enacted, French revolutionary politics evolved rapidly and developed into the Terror. She rejected this second phase because “equality has surpassed freedom,” disrupting the pre-existing social and economic order. Thus, in Staël’s political thought, the tension between freedom and equality is a central theme.

Staël is thus not just a female literary author, but also a historical philosopher who formulated liberal political thought in the form of a history of the French Revolution.

I analyzed the historical context that gave rise to de Staël’s historical interpretation of the French Revolution and her contribution to the liberal historiography of the French Revolution in “On a Liberal Interpretation of the French Revolution: Mme de Staël’s Considérations” in Generation of Mediation Politics: Germaine de Staël: Forging a Politics of Mediation, ed. by Karyna Szmurlo (SVEC volume 2011: 12. Oxford University Press).

My monograph, entitled Mme de Staël and Political Liberalism in France (Palgrave, 2018), addresses her liberal political thought from a more comprehensive perspective and its wide-spread influence on nineteenth-century French politics, public opinion and the historical interpretation of the French Revolution.

Click here for more information on these studies.

Staël and Romanticism

So far, I have explained the unique role that Staël played in the French Revolution as a political thinker and her influence over 19th century France. At the same time, Staël was also active in the fields of literature and literary criticism. More specifically, she contributed to the development of Romanticism in France.

Today, Romanticism is known as a cultural movement that took place across the whole of Europe in the first half of the 19th century, including Germany, England, and France. But the crucial role played by Germany in its historic emergence during the last decade of the 18th century cannot be overlooked.

August Wilhelm Schlegel, who was among the leading figures of early German Romanticism and later became a permanent tutor for Staël’s children, defined Romanticism as follows: ‘If intelligence can grasp in each isolated thing only part of the truth, this feeling, by embracing all things, perceives and penetrates everything in everything’.

Public Domain

Propelled by Napoleon’s political persecution in France, Staël eventually travelled to Germany, where she became acquainted with early German Romanticism through contact with prominent intellectuals, such as Goethe. As a result, the ‘deification of emotion’, a characteristic of early German Romanticism, also affects Staël’s later work.

For instance, the novel Corinne or Italy takes place in Italy. However, its strong focus on sensibility is heavily influenced by early German Romanticism. Staël’s cosmopolitan position that emphasizes exchange between different cultures would go on to bring force to individuals and nations and exert decisive influence over the making of nineteenth-century French Romanticism.

On Corinne or Italy, see also these articles.